religious-inquiries – volume01 Issue19

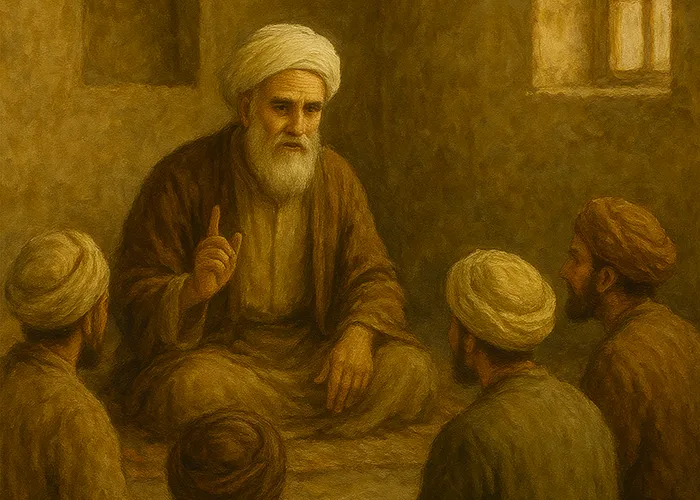

Imam Khamenei

Conditions for the Obligation of Enjoining Good and Forbidding Evil

Q1: If enjoining good and forbidding evil might compromise someone’s dignity or humiliate them publicly, is it still permissible?

A: If one adheres to the etiquette and boundaries of enjoining good and forbidding evil without transgressing limits, there is no issue.

Q2: Is it obligatory to have the capability to carry out enjoining good and forbidding evil? When does this duty become obligatory?

A: Enjoining and forbidding require knowledge of what constitutes good and evil, certainty that the wrongdoer acts intentionally and without a valid shar‘ī excuse. This duty becomes obligatory only if it is likely to be effective and free from risk of harm. If it poses potential harm, it is not obligatory.

Q3: If a relative is committing sins without care, should one maintain relations with them?

A: If breaking ties might deter the relative from sinning, it becomes obligatory to do so; otherwise, it is not permissible to cut kinship ties with blood relatives.

Q4: Is it permissible to avoid enjoining good and forbidding evil out of fear of losing one’s job, for instance, if a colleague in a university environment acts against shar‘īah, risking job security if confronted?

A: If considerable harm is likely to result from enjoining good and forbidding evil, the obligation does not apply.

Q5: If forbidding a sinner risks creating negative impressions of Islam but failing to do so might encourage others to sin, what should be done?

A: Enjoining good and forbidding evil, when conditions are met, are collective religious duties intended to protect Islamic principles and societal well-being. A potential negative perception of Islam by some individuals does not justify neglecting this critical duty.

(Source: Practical Laws of Islam – Imam Khamenei, leader.ir)

Ayatollah Sistani

Conditions for Enjoining Good and Forbidding Evil

Ruling 1: Five conditions make enjoining good and forbidding evil obligatory:

Knowledge of Good and Evil: One must generally know what constitutes good and evil. Thus, someone who lacks this knowledge is not obligated to perform this duty. Learning may become necessary as a prerequisite.

Probability of Effectiveness: It must be likely that enjoining or forbidding will influence the wrongdoer. If it is known that one’s words will not be effective, most jurists agree there is no obligation, though expressing disapproval remains advisable.

Intent to Persist in Wrongdoing: If the wrongdoer does not intend to repeat their action, there is no obligation to enjoin or forbid.

No Legal Excuse: The wrongdoer must lack a shar‘ī excuse; i.e., they must not believe the act they committed is permissible or that a good act they omitted is non-obligatory. However, if the act involves something profoundly displeasing to Allah, such as taking an innocent life, intervention becomes obligatory even if the wrongdoer is excused.

Absence of Significant Harm: The duty is void if enjoining or forbidding may lead to considerable harm to one’s person, reputation, or wealth unless the issue is deemed so significant by Allah that harm must be endured.

Ruling 2: The duty to enjoin and forbid is more critical with family and relatives. Therefore, if a family member neglects religious duties or engages in prohibited acts, they should be approached with a heightened sense of responsibility. However, with one’s parents, a gentle and respectful approach must always be taken.

(Source: Ayatollah Sistani’s rulings, sistani.org)

Ayatollah Makarem Shirazi

Principles of Enjoining Good and Forbidding Evil

Issue 1: Enjoining good (Amr bil Ma’roof) and forbidding evil (Nahyi ‘anil Monkar) are obligatory for all sane and adult individuals if these conditions are met:

The individual must be certain that the other party is committing a forbidden act or neglecting an obligatory one.

There should be a reasonable expectation of effectiveness, regardless of the timing or extent of the effect.

No harm should come to one’s life, reputation, or wealth due to this duty. However, in cases where protecting Islam’s core tenets is at stake, harm may be disregarded if it serves to uphold these essential principles.

Issue 2: When innovations (Bid’at) undermine Islam, all Muslims, particularly religious scholars, must declare the truth and renounce wrongdoing. If scholars’ silence would degrade the role of knowledge or cause public doubt, it becomes obligatory to speak out, even if effectiveness is uncertain.

Issue 3: Enjoining good and forbidding evil can be done with words, by avoiding the wrongdoer, or by adopting a stern approach without sin. If harsher measures are necessary, such as physical intervention, these actions require a Mujtahid’s permission and must align with established legal limits.

(Source: Ayatollah Makarem Shirazi’s rulings, makarem.ir)

editor's pick

news via inbox

Subscribe to the newsletter.